Venice Holds Back the Flood

- Editor OGN Daily

- Oct 7, 2020

- 3 min read

For the first time in 1,200 years, the city has successfully defended itself against flooding, courtesy of its new €5.5 billion defence system.

Sebastian Fagarazzi is used to moving his belongings around. As a Venetian who lives on the ground floor, every time the city faces acqua alta (the regular flooding caused by high tides) he must raise everything off the floor, including furniture and appliances, or risk losing it.

But last weekend, with a 135 cm (53 inch) high tide forecast - which would normally see around half the city under various levels of water - when the flood sirens went off, he did nothing. "I had faith," he says.

Saturday was the first acqua alta of the season for Venice. It was also the day when, after decades of delays, controversy and corruption, the city finally trialled its long-awaited flood barriers against the tide.

A previous trial in July, overseen by Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte, had gone well - but that was in good weather, at low tide. Earlier trials had not managed to raise all 78 gates in the barriers that have been installed in the Venetian lagoon.

At noon, high tide, St Mark's Square - which starts flooding at just 90 cm, and should have been knee-deep - was pretty much dry, with only large puddles welling up around the drains.

The square's cafes and shops, which often have to close for hours on end, remained open.

And in the northern district of Cannaregio, Sebastian Fagarazzi's home stayed dry. "I'd heard the [warning] sirens in the morning but I didn't raise any of my furniture this time because the barrier lifted on the last test, and I had faith that it would work," Fagarazzi, says. "This is historic."

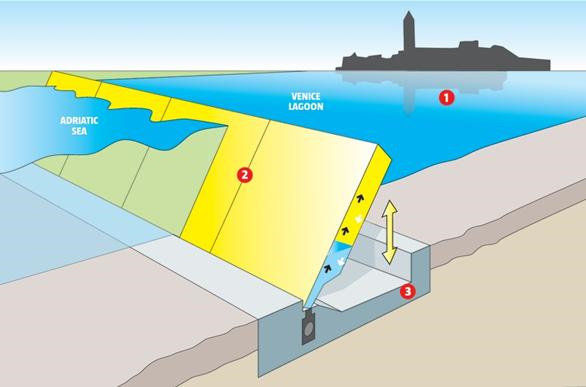

The defense system is called MOSE, the Italian for Moses, a name derived from the rather less snappy Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico. It consists of 78 flood barriers installed in the seabed at the lagoon's three main entrance points. When the high tide arrives, they can rise to form a dam, stopping the Adriatic Sea surging into the lagoon and flooding the city.

Venice's acque alte are normally seen between October and March, and last a couple of hours, predominantly affecting the two lowest (and most visited) areas of the city: San Marco and the area around the Rialto. The phenomenon is usually caused by a combination of exceptionally high tides, low atmospheric pressure and the presence of a southern sirocco wind.

In recent years, their frequency and severity have been increasing due to climate change. On November 12, 2019, the city was devastated by an acqua alta that reached 187 cm, with almost 90 per cent of the city flooding. Businesses have struggled to recover since, with a sharp dip in tourist numbers on top of damage costs.

The MOSE project has been in the works since 1984, but has been so beset by delays and corruption that many Venetians never believed it would work.

A test in poor weather conditions had been the next step for the MOSE, which is not yet completed. And on Friday, when a full moon and high winds were predicted for the following morning, the city council asked permission to raise the barriers. Against all the odds, it worked.

The usual flood sirens rang throughout the city at around 8 a.m. Saturday, while the test started half an hour later. By 10.10, the barriers were fully raised - and while the water level rose to 132 cm outside the MOSE, inside the lagoon, it remained at 70 cm - enough to keep San Marco dry.

"This was a historic day for Venice," Mayor Luigi Brugnaro, who had watched the raising of the barriers with MOSE special commissioner Elisabetta Spitz, later told journalists.

"There's a huge satisfaction, having spent decades watching helplessly as the water arrived everywhere in the city, causing vast amounts of damage. We have shown, not only with a tide that would have flooded the city but also with a sirocco wind of 19 knots, that it works."

Source: CNN